Gallery One

The main focus of Gallery One is the Golden Years of Sussex Cricket, 1895-1905.

The Golden Years of Sussex Cricket

These were the years of Ranji and Fry when Sussex supporters were treated to a batting feast. With small boundaries and for the most part a good batting wicket, opposing bowlers must have dreaded coming to Hove. Opposition bowlers would toil all day long to try and get first Fry and his opening partner, Joe Vine, out, before Ranji himself came in lower down the order.

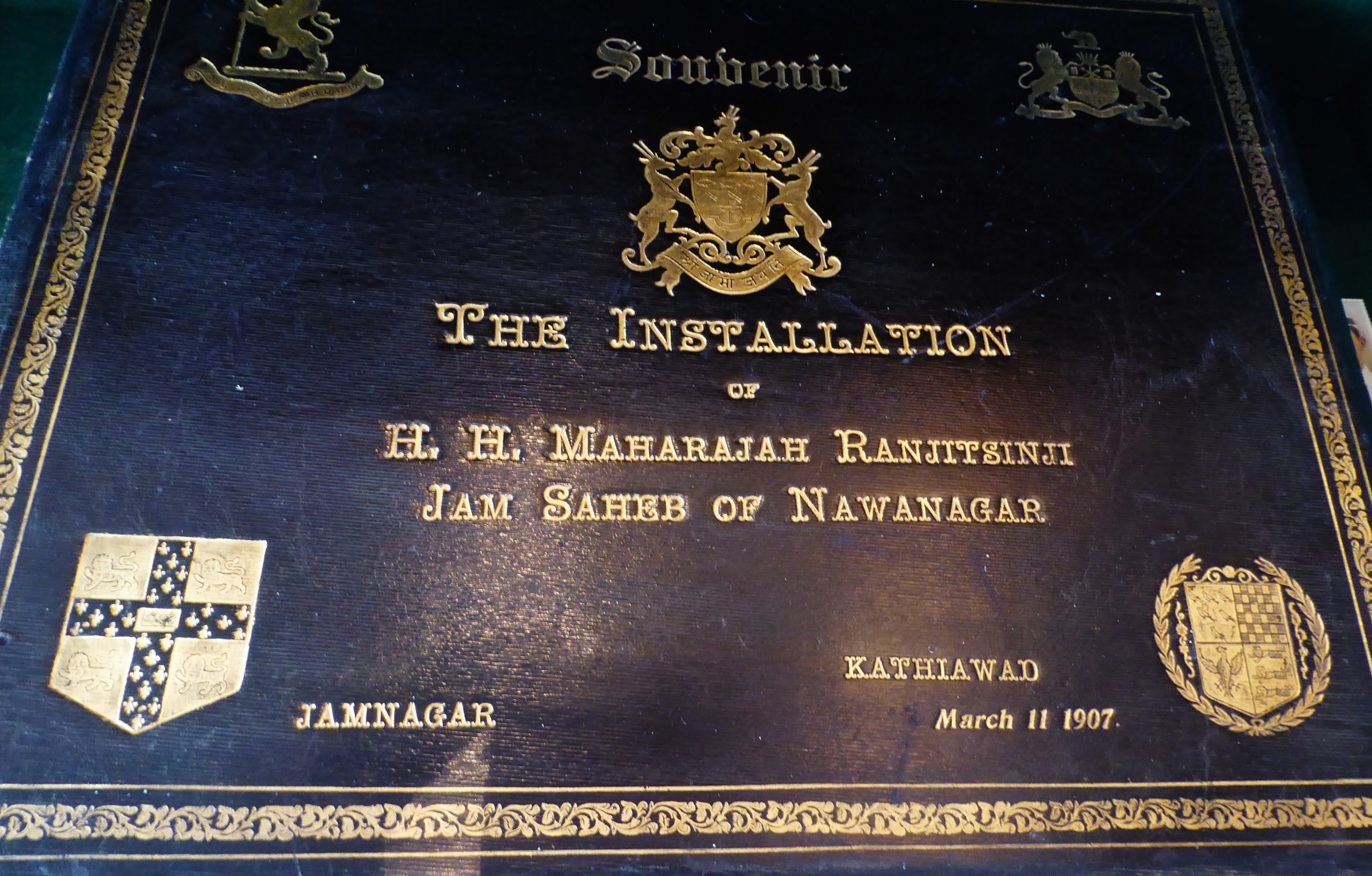

As you enter the gallery, on the left hand side is a cabinet full of Ranji memorabilia, including his Coronation album from 1907 donated by Ranji himself. In the same cabinet as the Ranji album is a bat once used by Harry Phillips to score a century against the 1884 Australians together with a photograph of Phillips with GN Wyatt (who also scored 100 in the first innings against Australia) and Walter Humphreys (who took 11 wickets including a hat trick in the same match).

On his debut for Sussex in May 1895, Ranji scored 77 and 150 against the MCC, and he was soon a regular in the Sussex side. Ranji had exceptional eyesight, and was very flexible with strong wrists which allowed him to glance a good length ball off the middle stump in a way that very few others could do.

His runs soon earned him selection for the England side in 1896, but not until there had been a debate about his eligibility. On the advice of Lord Harris, Ranji was not selected for the Lords Test match. At that time the host ground selected the England teams, so for the Second Test at Old Trafford he was selected (having first raised the matter with the Australians who raised no objections to Ranji playing). Ranji scored 62 and 154, so becoming only the second batsman after W.G. Grace to score a century on his Test debut.

In 1897/8 Ranji toured Australia and in the first test scored 175 even though he had been ill. From then until 1902, he was a regular in the England side, scoring 989 runs in fifteen tests for his adopted country, at average of 44.95. It was though for Sussex that he made the majority of his runs. In 1896 he made 2,780 runs with 10 centuries and in 1899 scored 3,159 runs with eight centuries, becoming the first batsman to score over 3,000 runs. He repeated the feat in 1900 and in then in 1905 scored 2,077 runs.

Overall, Ranji scored 1,000 runs in twelve seasons, and captained Sussex between 1899 and 1903. In total for Sussex he scored 18,594 runs between 1895 and 1920 at an average of 63.2 with a top score of 285no against Somerset in 1901.

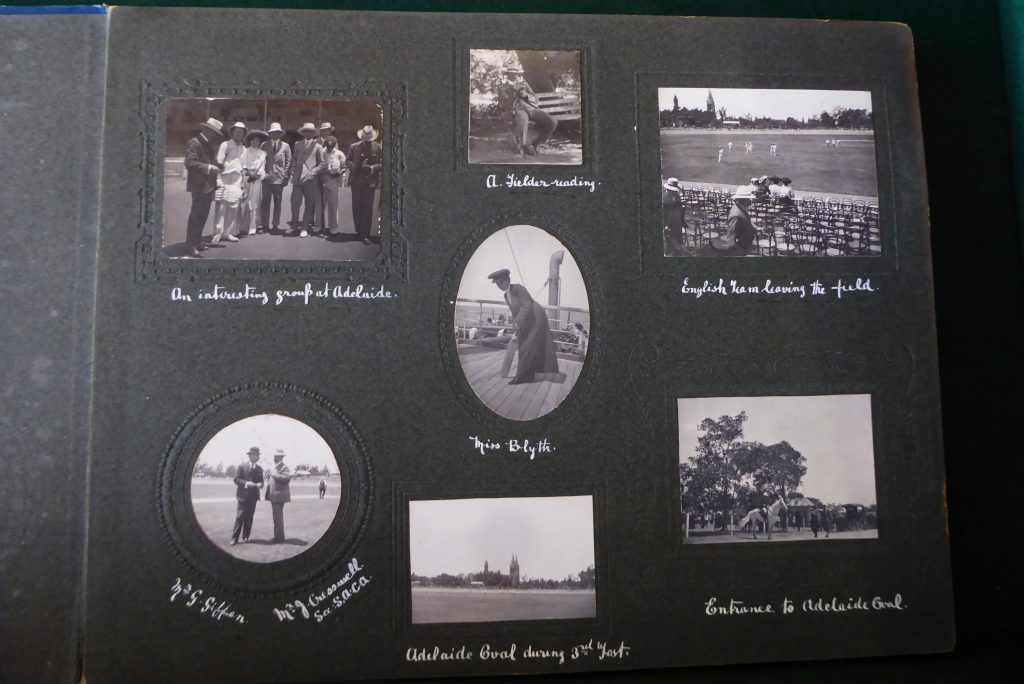

In the second section of the cabinet is a diary and photograph album that Bert Relf compiled whilst a member of the MCC team in Australia in 1903-4, together with a watch, leather wallet and napkin ring that all belonged to Bert. There is also a bat signed by many Sussex players from the 1901 side. The watch Bert received for playing for Lord Londesborough’s XI against Australia at Scarborough in September 1912.

Bert was Sussex’s leading all-rounder in the first twenty one years of the c20th. When he began his career with Sussex in 1900 he was already a seasoned player, having been coached by his father at Wellington College. He qualified for Norfolk before joining the Lord’s ground staff and then in 1900 scored 96 on his debut for Sussex against Worcestershire.

Although he lacked technical finesse, he made far more runs than other more elegant batsmen. Between 1902 and 1914 he exceeded 1,000 runs in eight seasons and had the unusual distinction of participating in century partnerships for every wicket down the order. He was an excellent slip fielder but was to make his mark as a bowler. By 1903 he was heading the bowling averages with 108 wickets in all matches. He achieved 100 wickets in a season on a further nine occasions, achieving the double of 100 wickets and 1,000 runs in six seasons between 1905 and 1913. He bowled at medium pace off a short run and was able to move the ball both ways. Having such a short run up he was able to bowl long spells.

On the right side of Gallery One there is a cabinet on CB Fry which includes a well-worn Oxford University sweater donated by Fry to the Sussex Cricket Library (now the Sussex Cricket Museum) just before he died in 1956. Fry said of the sweater ‘’I wore that in 1901. It was rather a cold summer’’. Mr Melville, the then Librarian, asked whether that was the only reason Fry could remember the sweater for in that season Fry had set a record of six centuries in six successive innings as well as scoring more than 3,000 runs.

Fry joined Sussex in 1894 and when Ranji joined a year later large partnerships between the two of them became regular features of Sussex games. The two men showed contrasting styles with the technically correct Fry against the wristy strokes of Ranji. Fry liked to study the technical aspects of the game and his powers of concentration enabled him to dominate most bowlers. He had an excellent defence and a good straight drive and was particularly adept at working the ball away on the offside.

Between 1899 and 1905 Fry scored 2,000 runs a season on six occasions, and in 1901 scored over 3,000 runs (3,147) with 13 centuries including six successive centuries. In the eight seasons from 1898 Fry was twice first in the national averages, and four times second. From 1901 he began a solid opening partnership with Joe Vine, with Vine playing the anchor role.

On the right have a look at the Tea Service within the wooden cabinet, given by Ranji to William Murdoch’s wife, Jemina for Christmas 1896.

Hanging on the wall take a look at the image of the ground just before WW1 and work out which parts of the ground are still there.

To the left of the door there are photos of Ranji including one taken when Ranji took part in a memorial service at the Cenotaph along with George V. Ranji’s jacket is also in the cabinet. On the next wall is a large image of Ranji at the crease.

A recent addition to the gallery is a fully restored large silk handkerchief, dating from the 1760s, which shows the laws of cricket as they existed in books and magazines from that time. Inscribed in the bottom right corner are the words Jos Ware, Cranford indicating the name and location of the factory that produced the handkerchief.

In the c18th,the use of such handkerchiefs for hygienic purposes was confined to the upper echelons of society, and given they were often made of the finest silks and linen, were often made for decorative or commemorative purposes. These very early handkerchiefs were made of silk often with a cricket theme and were produced by Joseph Ware of Crayford in Kent and showed the earliest printed laws of the game. Joseph Ware took over the calico works in 1757 and ran the firm until 1769. Just four of the handkerchiefs produced at the Ware factory are still in existence and Col. RS Rait Kerr in The Laws of Cricket Their History and Growth (1950) concludes that the handkerchief in the Sussex Cricket Museum is the earliest of the four produced by the Cranford factory to have survived. One is in the museum at Melbourne Cricket Club, two are in the museum at Lord’s and the other is on display in the Sussex Cricket Museum.

Also on display in the Museum, in the alcove in Gallery Three, is an early screen that was once used by David Evans at his silk printing factory at Crayford to produce silk scarves that were copies of c18th handkerchiefs. The firm, established in 1843, was once Europe’s most fashionable manufacturer of such handkerchiefs and survived until 1921 when the Museum’s screen was acquired by Mrs Janet Hearn-Gillham who subsequently donated it to the Sussex Cricket Museum.